"Dan-Joe & Malcolm (WW1)" -- TOC

Ch. 15 - "Passchendaele: November, 1917"

For the first part of November, 1917, Dan-Joe's Battalion was in a Rest Area. It was a "rest area"; but it was also a training area. What had developed, as a principal training exercise, was, to run the soldiers with their leading officers over taped courses in an open field. The terrain that they expecteed to go over was duplicated by using coloured tape to measure out and show distances between the obstacles expected (such as known trenches, hillocks, etc.). The Canadians were being readied for another job. They were well known by the British commanders as soldiers who got things done, especially when it came to gaining ground on the Germans.

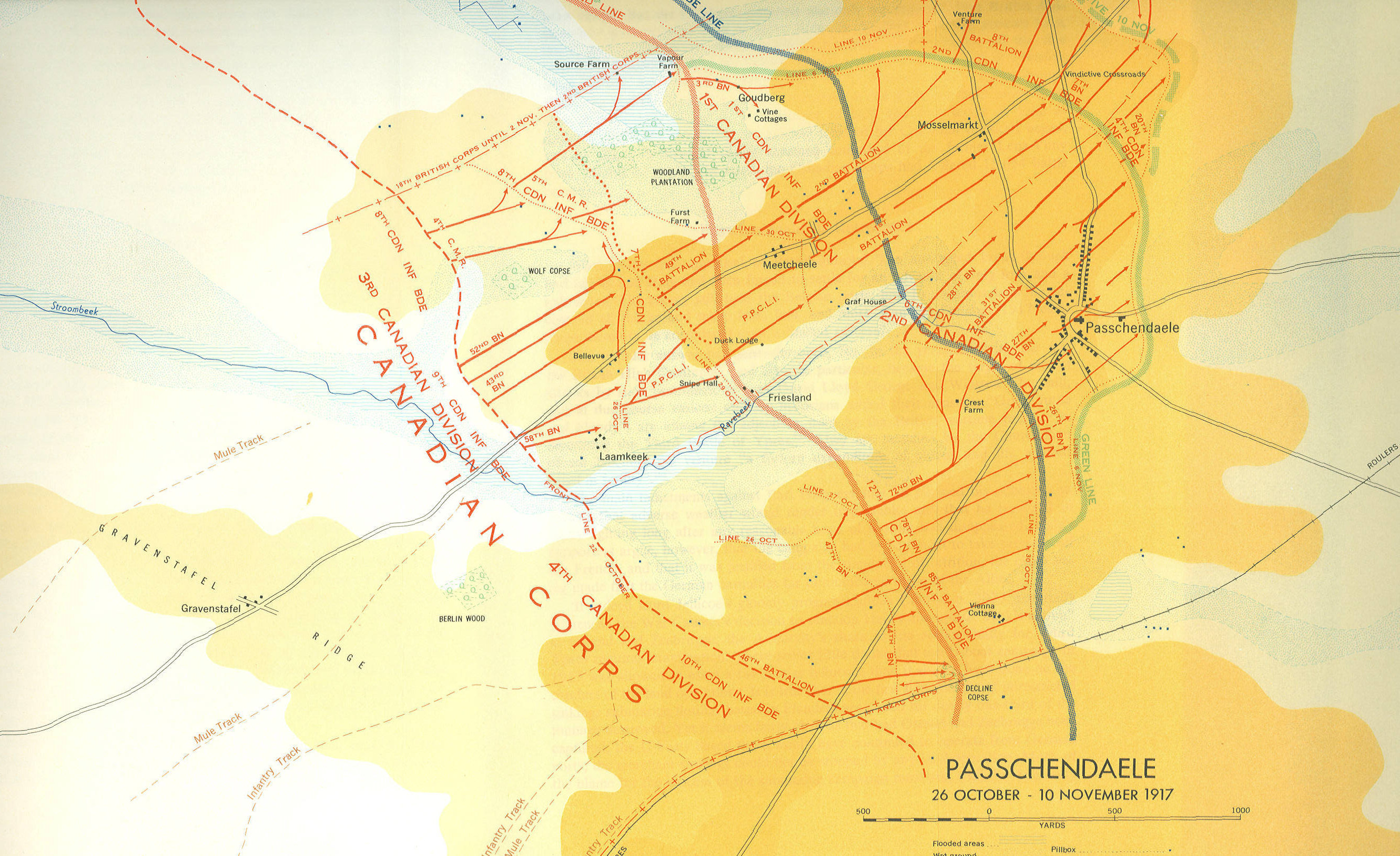

On the 3rd of November, Dan-Joe's battalion with others (collectively known as the 2nd Canadian Division) went by train from Caestre to Ypres and marched to Potijze." On the 4th, stores were drawn and issued; on the 5th, they were at the Assembly Area. A message came through: "Zero hour will be 6:00 A.M., November 6th." At this appointed hour, the Canadians charged the German positions at Passchendaele, about 2,000 yards away. The diary, shows, that before the day was out, a call was made for a "Stretcher Party of 100." The bodies of the wounded and killed were spread over the cratered mud between the originating Allied trench line to the German objective; the Canadians had made it, but at a horrendous cost.

The Battle for Passchendaele began in October, 1917; it continued to the 6th of November, when the Canadians captured what was left of Passchendaele village.82 The cost to the four divisions of the Canadian Corps (1st, 2nd [Dan-Joe's], 3rd and 4th) was 15,634 killed and wounded, a figure predicted by Arthur Currie, the commander of the Canadian forces in France.83

Let us turn to an accounting of the great odds which the Allies faced given by Philip Gibbs, 1877-1962, an English journalist at the front. We quote:

"In front of us was not a line but a fortress position, twenty miles deep, entrenched and fortified, defended by masses of machine-gun posts and thousands of guns in a wide arc. ...

Before dawn there was a great silence. We spoke to each other in whispers, if we spoke. Then suddenly our guns opened out in a barrage of fire of colossal intensity. Never before, and I think never since, even in the Second World War, had so many guns been massed behind any battle front. It was a rolling thunder of shell fire, and the earth vomited flame, and the sky was alight with bursting shells. It seemed as though nothing could live, not an ant, under that stupendous artillery storm. But Germans in their deep dugouts lived, and when our waves of men went over they were met by deadly machine-gun and mortar fire.

Our men got nowhere on the first day. They had been mowed down like grass by German machine-gunners who, after our barrage had lifted, rushed out to meet our men in the open. Many of the best battalions were almost annihilated, and our casualties were terrible.

A German doctor taken prisoner near La Boiselle stayed behind to look after our wounded in a dugout instead of going down to safety. I met him coming back across the battlefield next morning. One of our men were carrying his bag and I had a talk with him. He was a tall, heavy, man with a black beard, and he spoke good English. 'This war!' he said. 'We go on killing each other to no purpose. It is a war against religion and against civilisation and I see no end to it.'"84

On the 12th of November, the battle-weary soldiers were given an extra special break that they all undoubtedly deserved - "officers and men given leave to surrounding towns, many taking advantage and renewing acquaintances with inhabitants, most particularly Gaby And Julie At Renningelst. Numerous Graves of fallen comrades were visited and all found to be well kept up." Through the 13th to the 16th the men were marched and bused away some distance from the dreadful scene at Passchendaele to a place just 10 kms northwest of Arras: Villers-au-Bois where a camp was located. The comment was that this camp was "spotlessly clean." There the men were addressed "by the Commanding Officer [Lt-Col. McKenzie] on the good work at Passchendaele by the Battalion." This place, the camp at Villers-au-Bois, was referred to as the "Divisional Reserve." There the men of the 26th continued with their perpetual army exercises: "Battalion Parade, training, saluting, marching and Squad Drill." This lasted only so long as by the 22nd the men were returned to the familiar trenches not far from an earlier successful battle at Vimy. There, in the trenches, we see, for the next couple of days that "Usual work carried on improving trenches." More reinforcements come in during this time to fill up the decimated ranks. The "situation quiet." By the 29th of November the battalion was once again "in Divisional Reserve. Kit Inspection and Pay Parade in morning. Baths and Pay in afternoon."

The Canadian success at Passchendaele85 November, 1917, and for that matter at Vimy in April, 1917, were well noted: in the result "the Canadian Corps was regarded by friend and foe alike as the most effective Allied military formation on the Western Front. The Germans went so far as to call them 'storm troopers.'"86

Or, GO TO

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Peter Landry

2015